Lambdavacuum solution

In general relativity, a lambdavacuum solution is an exact solution to the Einstein field equation in which the only term in the stress-energy tensor is a cosmological constant term. This can be interpreted physically as a kind of classical approximation to a nonzero vacuum energy.

Terminological note: this article concerns a standard concept, but there is apparently no standard term to denote this concept, so we have attempted to supply one for the benefit of Wikipedia.

Contents |

Mathematical definition

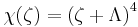

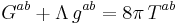

The Einstein field equation is often written, with a so-called cosmological constant term, as

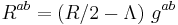

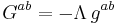

However, it is more sensible to move the extra term to the right hand side and absorb it into the stress-energy tensor, so that the cosmological constant term becomes just another contribution to the stress-energy tensor. When other contributions vanish,

we have a lambdavacuum. Equivalently, we can write this, in terms of the Ricci tensor, in the form

Physical interpretation

A nonzero cosmological constant term can be interpreted in terms of a nonzero vacuum energy. There are two cases:

: positive vacuum energy density and negative vacuum pressure (isotropic suction), as in de Sitter space,

: positive vacuum energy density and negative vacuum pressure (isotropic suction), as in de Sitter space, : negative vacuum energy density and positive vacuum pressure, as in anti-de Sitter space.

: negative vacuum energy density and positive vacuum pressure, as in anti-de Sitter space.

The idea of the vacuum having an energy density might seem outrageous, but this does make sense in quantum field theory. Indeed, nonzero vacuum energies can even be experimentally verified in the Casimir effect.

Einstein tensor

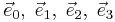

The components of a tensor computed with respect to a frame field rather than the coordinate basis are often called physical components, because these are the components which can (in principle) be measured by an observer. A frame consists of four unit vector fields

Here, the first is a timelike unit vector field and the others are spacelike unit vector fields, and  is everywhere orthogonal to the world lines of a family of observers (not necessarily inertial observers).

is everywhere orthogonal to the world lines of a family of observers (not necessarily inertial observers).

Remarkably, in the case of lambdavacuum, all observers measure the same energy density and the same (isotropic) pressure. That is, the Einstein tensor takes the form

Saying that this tensor takes the same form for all observers is the same as saying that the isotropy group of a lambdavacuum is SO(1,3), the full Lorentz group.

Eigenvalues

The characteristic polynomial of the Einstein tensor of a lambdavacuum must have the form

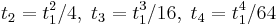

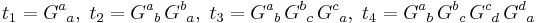

Using Newton's identities, this condition can be re-expressed in terms of the traces of the powers of the Einstein tensor as

where

are the traces of the powers of the linear operator corresponding to the Einstein tensor, which has second rank.

Relation with Einstein manifolds

The definition of a lambdavacuum solution makes mathematical sense irrespective of any physical interpretation, and lambdavacuums are in fact a special case of a concept which is studied by pure mathematicians.

Einstein manifolds are Riemannian manifolds in which the Ricci tensor is proportional (by some constant, not otherwise specified) to the metric tensor. Such manifolds may have the wrong signature to admit a spacetime interpretation in general relativity, and may have the wrong dimension as well. But the Lorentzian manifolds which are also Einstein manifolds are precisely the Lambdavacuum solutions.

Examples

Noteworthy individual examples of lambdavacuum solutions include:

- de Sitter lambdavacuum, often referred to as the dS cosmological model,

- anti-de Sitter lambdavacuum, often referred to as the AdS cosmological model,

- Schwarzschild–dS lambdavacuum, which models a spherically symmetric massive object immersed in a de Sitter universe (and likewise for AdS),

- Kerr–dS lambdvacuum, the rotating generalization of the latter,

- Nariai lambdavacuum; this is the only solution in general relativity, other than the Bertotti–Robinson electrovacuum, which has a Cartesian product structure.

![G^{\hat{a}\hat{b}} = -\Lambda \, \left[ \begin{matrix} -1&0&0&0\\0&1&0&0\\0&0&1&0\\0&0&0&1\end{matrix} \right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/c2a7ddc719d57d6b7b4c509d30c9efc7.png)